The trouble is, every word has a particular meaning, but this meaning must be subordinated to the meaning of the sentence -- and then sentence to paragraph, paragraph to chapter, chapter to narrative, etc.

I remember once reading in a Scientology pamphlet of L. Ron Hubbard's advice to his clones on how to approach a difficult text. To the extent that you don't understand it, just look up each unknown word in the dictionary, then put it all together. Voila! Meaning.

I've never tried the method, but it would probably be impossible even for simple sentences, because you'd just end up with more autonomous parts without getting any closer to the integral meaning.

I'm tempted to try....

Okay: "I live in a house."

To streamline this, I'll just use the first definitions.

"Someone possessing and aware of possessing a distinct personal individuality am alive -- i.e., have the life of an animal or plant -- in a location or in space or in some materially bounded object, in this case a structure intended or used for human habituation."

But then you'd have to look up possessing, distinct, individuality, materially, structure, etc. Thus, the Hubbard Method just makes things more convoluted, not easier. Plus -- like the dictionary itself -- it is ultimately tautologous. That is, words just refer to other words, in a closed logoverse. For example, my Oxford dictionary couldn't even define "in" without using the word. Ultimately you probably couldn't say a thing without literally involving the whole dictionary.

More generally, knowing the meaning of words is an entirely different function from using them well in a sentence. In fact, using them well often involves using them incorrectly. I recently read a biography of Wodehouse, in which the author wrote the following very Wodehousian sentence: "To this day, even as a peacetime museum, it broods menacingly over the tower of Huy..." If you were to deploy the Hubbard Method to deconstruct the sentence, you'd be left with the impression that inanimate buildings are subject to moods and intimidating gestures.

Wodehouse habitually tossed in bizarre personifications, e.g., As I sat in the bath tub, soaping a meditative foot and singing..., or He uncovered the fragrant eggs and b., and I pronged a moody forkful..., or Unseen, in the background, Fate was quietly slipping the lead into the boxing gloves, etc. There are hundreds if not thousands of these.

This is a long way of asking the question: how would it even be possible to understand scripture if we didn't already understand it?

A more basic problem, it seems to me, is how words -- and language more generally -- get outside themselves? Again, if words just refer to other words, then they cannot refer to God, except in the form of another word.

The short answer is of course provided by the pneumanaut with the umlaut, Gödel. He proved once and for all that any logical system contains assumptions that cannot be justified by the system. Rather, we need the assumptions to get off the semantic goround.

As we've discussed before, postmodernists completely misunderstand this to mean that there is no possibility of real meaning, but Gödel's whole point -- at least according to Goldstein -- is that there are truths that cannot be proved logically. He didn't intend to abolish truth but preserve it.

It also means that, whatever our minds are, they cannot be digital computers, because they always transcend the digits. His theorems "don't demonstrate the limits of the human mind, but rather the limits of computational models of the human mind (basically, models that reduce all thinking to rule-following)" (Goldstein).

Otherwise, Gödel's theorems would disprove Gödel's theorems. As we mentioned a couple of posts back, man breaks out of his animal form and opens out to the infinite, "beyond the circumscriptions of personal experience to gain access to aspects of reality that it is impossible to otherwise know" (ibid.).

So language, in order to get beyond itself, must be a vertically open system in which something from beyond the system is able to infuse the words with a meaning and a Life which they alone cannot convey.

Gödel -- unlike positivists at one end and deconstructionists at the other -- "is committed to the possibility of reaching out... beyond our experiences to describe the world 'out yonder.'" This yonder world is a reality "of universal and necessary truths" to which we are mysteriously -- and sometimes mythteriously -- able to gain access. As a result, we may gain "at least partial glimpses of what might be called... 'extreme reality.'"

Yesterday, out of the blue, my son surprised me by reeling off pi to eight or ten decimals. What does it mean that the ratio of the circumference of a circle to its diameter is a deeply irrational number that goes on forever? The circle has always been considered the "perfect" form, so it was troubling to the ancients that pi brooded so menacingly over them.

Schuon often deployed the geometrical circle as a point of reverence to make theometrical statements about God. For example, if God is the center of the circle, we are at the periphery. Looked at this way, the center is surrounded by concentric circles corresponding to this or that worldspace, e.g., life, mind, matter, angels, archetypes, etc. Some worlds are necessarily closer to or more distant from God. Evil is way out there.

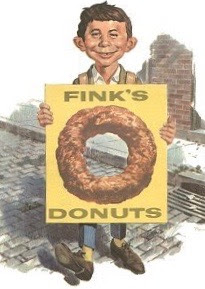

But it can also be used the other way around, such that the world is within the circle and the infinite God surrounds it (like the mysterious "man in the donut" in the sidebar).

To put an impatient kibosh on this scatterish post, "The man who does not believe in God must read Scripture differently from the man who does.... a discussion between them as to the meaning of the New Testament is as though one were discussing marriage with a eunuch" (Sheed).